This was going to be a watershed moment, the one that the entire country was waiting on pins and needles for – because the network dweebs told us so. Superstar, enigmatic running back was going to say a few words, so the camera was positioned, and the microphone thrust at his lips. Videotape whirred and was ready to capture the bon mots forever onto the magnetized ribbon.

Duane Thomas was a running back who had, frankly, only one good season. He was like the Russia that had once been described as being a “riddle wrapped inside an enigma.” Extremely talented, but not always caring to put those talents to use. We media folks have always been fascinated with his type – the athlete who could be so good, if he’d only tap into his pool of skill and raw ability.

Thomas carried the ball for the Dallas Cowboys, and later the Washington Redskins. In between there was a stop with the San Diego Chargers, but the riddle/enigma couldn’t be persuaded to suit up for even one game for them. He was a man with issues. Something was the matter all the time.

In 1971, Thomas took a vow of silence, using the NFL as his monastery. Something was the matter again. So there would be no speaking to anyone – not the media, not to his teammates, not to his coaches. His contract, after all, called for ball carrying – not conversation.

Thomas in typical repose

Throughout the season, Silent Duane fulfilled the ball carrying part of his pact quite well. He rushed for nearly 800 yards and scored 11 touchdowns. Yet through it all, he was mum. He made his stone-faced, button-down coach Tom Landry look like a chatterbox.

The Cowboys made it all the way to Super Bowl VI behind Thomas’s ball carrying, and whipped the Miami Dolphins. Thomas starred in the big game, too – carrying the ball 19 times for 95 yards, and scoring a touchdown. Then, afterward, word got out to the network dweebs that Thomas was going to speak.

Duane Thomas is going to talk!

As champagne flowed and players whooped and hollered in the background, Silent Duane was directed to the makeshift TV stage, elevated above everyone else. The camera was trained on him, the microphone inches from his rusty mouth.

“Duane, you had a great game today,” the announcer blabbed in so many words, “looks like your team really had the running game going.”

Thomas, a twinkle in his eye, then spoke.

“Evidently,” he said.

End of interview.

Rarely has one word on live television made so many network dweebs gag. Unless that word started with an “F.”

That was it – the extent of Duane Thomas’s verbosity in 1971.

“Evidently.”

Thomas was out of football by 1975 after two unspectacular seasons with the Washington Redskins. Something was the matter again, and this time football wasn’t going to be his monastery anymore.

*****************************************

Steve Carlton was, for my money, the best left-handed pitcher since Sandy Koufax. He managed to win 27 games in 1972, for a horrid Phillies team that had only won 59 as a team. Sometime in the mid-1970s, stung by what he considered to be poor treatment by the press, Carlton took a Thomas-like vow of silence. But Carlton’s lips would only remain zipped with the media. Apart from them, he’d engage anyone else in discussion.

Years of this went by. The muteness of Carlton became winked at – a contemporary legend that was being lived out in a modern day’s world of aggressive reporting and growing electronic media.

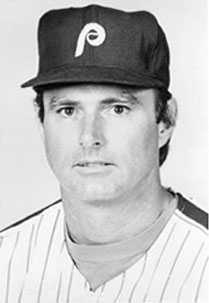

Carlton didn't speak to the media for the last two decades of his career

And it was only relevant because Steve Carlton was a dominant pitcher. Nobody usually cares if the bench warming player goes quiet, after all.

And that’s the way it stayed, right until the end of Carlton’s 24-year big league career. He pitched, he showered, he got dressed, he left. It became accepted behavior, if not celebrated.

But today you can’t get a guy not to talk – at least not for very long. The media is intoxicating to today’s athlete. Rarely is silence a weapon of choice. Usually a war of words is the way to go. Today’s players are drawn to the tape recorders and cameras the way bugs are to light. Or, probably more appropriately, the way flies are to … whatever flies are attracted to.

It’s not always a bad thing.

Gary Sheffield came to the Tigers with a reputation that preceded him by fifteen minutes of infamy. He’d been some places before, and there tended to be some sort of acrimony at just about every stop. But if you think all the stories were true and unembellished, then I’d like to interest you in a book called, “Duane Thomas’s Greatest Quotes.”

Sheffield started this season in a slump. He’s still not out of it. In the throes of it about ten days ago, I approached him as a mole for Michigan In Play! Magazine, somewhat warily, as he walked away from the batting cage.

“Got a few minutes to talk?”

“Sure.”

And for the next ten minutes, Sheffield regaled me at his locker. He patiently, warmly, and with humility talked about his horrible slump. He’s always been a slow starter. He can’t explain why. He wants to show the fans that he was worth the trade – and the dough that accompanied it. He’s not panicking. He thinks the team is very good, the camaraderie marvelous.

“A couple of homers and five ribbies today, right?,” I said, ending our discussion.

He smiled broadly. “Absolutely.” Then we both chuckled.

Sheffield went 0-for-5 that day, including a crucial strikeout in the tenth inning of a tough loss to the Royals. The slump continued for another day.

But he had spoken about it, hadn’t hidden from it. He didn’t pull a Duane Thomas or Steve Carlton.

Few of them do, anymore. It’s too hard.

No comments:

Post a Comment