You don’t have to tell me that returning kicks in the NFL is sport’s version of Russian Roulette.

I know it’s a job that must have originally been given to the loser of a bet, or to the last man to arrive at the field before kickoff.

I’m well aware that the return man is a staph infection, and the 11 men on the kicking team are penicillin.

It’s not an easy gig, by any means. Yet, I find it incumbent to complain about the lack of quality return specialists employed by the Detroit Lions since the 21st century began.

But my crabbing isn’t solely done just to vent or to be contrary. There is a distinct cause and effect between the Lions’ return game and their overall lack of success.

The Lions start every possession in bad field position, it seems. They haven’t had anyone who can move the ball north of the 20 yard line on kickoffs with any consistency since slippery eels like Glyn Milburn and Mel Gray wore Honolulu Blue and Silver.

That was a long time ago.

Punt returning is a similar joke. With the Lions’ return men of late, a fair catch is a victory.

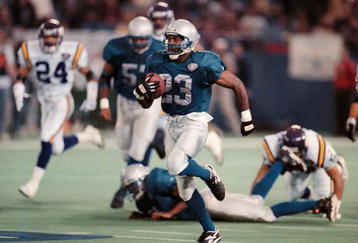

(Todd Rosenberg/Getty Images)

![]() It didn’t used to be that way. In fact, even when the Lions were bad before Matt Millen (and they were), at least we had kick returns to look forward to.

It didn’t used to be that way. In fact, even when the Lions were bad before Matt Millen (and they were), at least we had kick returns to look forward to.

Some of the most electrifying kick returners in NFL history have worn the Lions’ colors.

It takes a different type of man to agree to return punts and kickoffs. And when I say different, I mean totally nuts, cuckoo, off his rocker, stark raving mad.

There isn’t anything quite like it in sport, returning kicks, unless you’re going to count being a tennis ball, a hockey puck, or anything else that gets smashed and smacked around a playing surface.

The return man must first show no regard for his own health, or for his anatomy as God originally designed it. He must have the gene of a skydiver who knows his chute was put together by gorillas, yet decides to jump out of the plane anyway.

Let’s take kickoffs, or as they could otherwise be called, Human Demolition Derbies.

The kicking team races as fast as it can down the field, after getting a running start before the kicker’s foot even connects with the ball. We’ll call them Train A.

The return team chugs ahead, sometimes joining hands—perhaps for comfort and support—and strives to gain momentum. We’ll call them Train B.

The return man catches the football and aims to go from zero to 60 in less than five seconds. We’ll call him the Pinball.

Train A and Train B collide, and the Pinball tries to slither through the mayhem and emerge intact. Sometimes he does and he’s the one sprinting toward the end zone, running as if his pants are on fire.

But most times he gets clobbered by the effects of the wreckage from Train A and Train B colliding, and he’ll be the one planted into the turf somewhere near the 20 yard line.

The return man knows he has 11 men trying to get on SportsCenter and trying to impress coaches—all they have to do is clean his clock with a hit designed to knock the wind out of his body and halfway to Timbuktu.

So that’s the kickoff.

It gets worse.

The punt return man is often not the same as the kickoff return man, because usually he’s even crazier.

NFL punters are trained to boot the football high and far. While the rest of his teammates practice real football, the punter spends hours doing nothing but kicking footballs high and far. The higher and farther, the better.

Especially higher.

The higher the kicked ball, the more “hang time” it has, the more time the punter’s 10 comrades on the field have to think of how hard they’re going to blast the returner.

Here’s why the punt returner is even more looney tunes than the kickoff return guy.

The punt returner can’t do a damn thing until the football falls into his arms after its high, far journey through the air. The thundering herd of kicking team members can be heard and felt, yet all the punt return man can do is wait for the football and say some Novenas.

After he catches the football, the punt returner has less than a second, roughly, to figure out where the heck he wants to take it. He is charged with finding holes through which to run, in a split second with 10 screaming banshees running down the field hoping to place him in an NFL Films highlight reel for the ages.

It’s no wonder that you so often see the punt returner actually run backwards initially, toward his own end zone. Call it survival instinct.

I’ve always wanted to know what’s going through a punt returner’s mind as he waits for the football to fall from the sky, knowing what awaits him after he catches it.

So you see, I know it’s not the most desirable of vocations. Returning kicks is like jaywalking at the Indianapolis 500.

But the Lions used to have some great return men.

In the 1960s, there was Bobby Williams and Lem Barney, who was Deion Sanders before Deion was out of diapers.

Barney played into the 1970s, dazzling us with return feats of amazement.

In the 1990s, the Lions had Mel Gray, who was the only return man I’ve seen who was made of mercury. In six seasons with the Lions (1989-94), Gray took seven kicks back for touchdowns, including three kickoffs in ’94 alone.

After Gray came Milburn, who wasn’t quite as effective as Gray, but who was a legitimate threat to break free.

In the 2000s, the Lions have been returning kicks politely. Their return men frequently collapse to the ground easily. They’ve been as elusive as a turtle, and as slippery as flypaper.

In 2010, there’s a new kid back there fielding kickoffs. His name is Stefan Logan and he’s the size of a matchbox. Maybe the Lions are hoping it’ll be 20 yards before anyone finds him, let alone tackles him.

Logan had one decent return last Sunday, just before halftime—and just before the ill-fated sack of QB Matthew Stafford. Beyond that, he didn’t show me much.

None of them have, for more than a decade now.

No comments:

Post a Comment